The evolution of the Saudi House and traditional living

May, 2020

Housing typologies in Riyadh

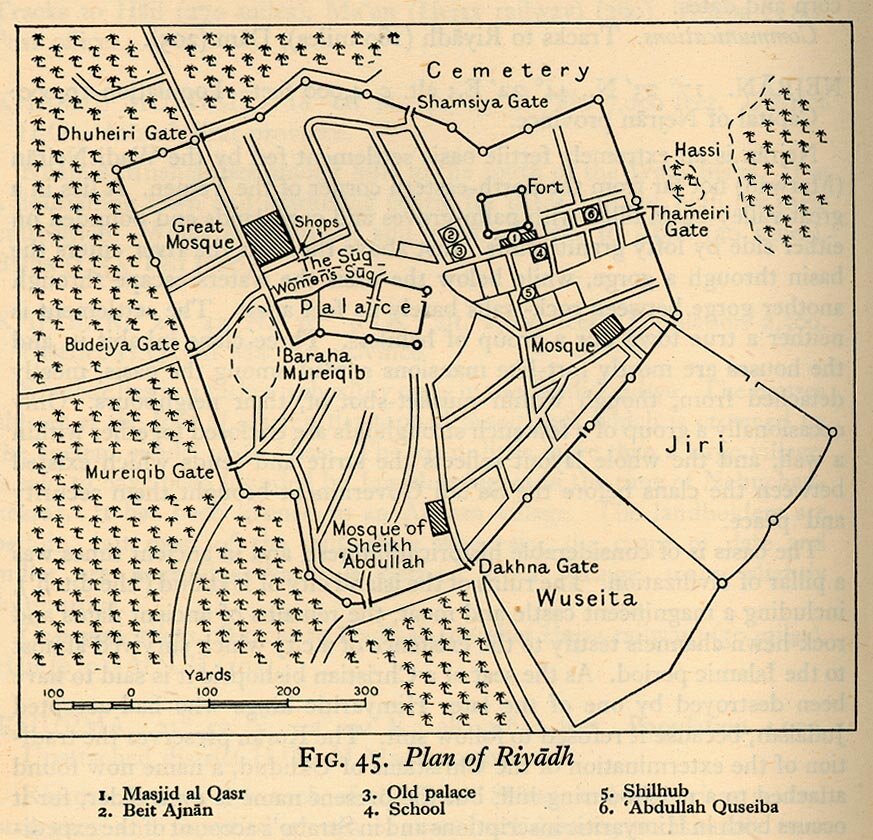

In 1902, Riyadh was reinstated as the center of the Saudi state by the founder King Abdulaziz Al Saud. Prior to that, it consisted of small communities situated along Wadi Hanifah. The one-square-kilometer city at the time had a population of fourteen thousand residents and was fortified by mud and stone walls. Residential spaces in the old city consisted of clusters of adobe mud houses situated around the justice palace and the Imam Turki mosque.

Towards the end of the 1930s, the physical transformation of Riyadh began with the addition of AlMurabba complex which introduced the residential area of Alfutah that still remains until today. This has led the city to expand north beyond the existing walls by the end of the decade. Houses then were mainly characterised by square or rectangular forms arranged around courtyards that regulate the interior micro-climate. They were also built with shared sidewalls with small openings on the exterior facade to allow air circulation into the court while maintaining privacy.

In the 1950s, King Saud’s Nasiriyyah palace was considered by many as the first building in Riyadh in which reinforced concrete was used. During that time, government agencies were transferred to Riyadh and a housing project that introduced 754 detached dwelling units and three apartment buildings was underway in AlMalaz. The project also introduced for the first time the gridiron pattern of streets, square lots, and setbacks on all sides. The Malaz housing project set the tonality for future neighborhoods as the city continued growing into the early 1960’s along Al-Thumairi, Al-Wazir, and Al-Khazzan streets. Among those first apartment buildings was a six-story building of Fahd bin Muhammad overlooking AlAdel square.

By the end of 1960s, a masterplan of the city institutionalized the super-grid as the most desired pattern to be followed in its planning. The increase in horizontal expansion and the continuation of larger sized plots resulted in standardizing the villa, as the favorable housing typology.

Riyadh experienced considerable change through the 1970s/80s in social and urban contexts as a result of the economic boom. This has consequently led to a significant growth in the construction industry where the city eminently transformed from vernacular architecture to modern urban dwellings. During this period buildings were constructed with the aim to revitalise the architectural environment, the General Organization for Social Insurance housing project remains as testimony to those efforts. The expansive development during this period also expressed the modernist approach adopted by several local architects at the time. Among these prominent housing projects was the Ministry of Foreign Affairs housing completed in the early 1980s. Albert Speer & Partner designed an array of medium to high density accommodation that consisted of villas, attached & semi-detached dwellings in plot sizes ranging from 1000 sqm down to 175 sqm per unit. Thirteen design variations were produced as dwelling-types with the evident influence of Najdi architectural elements such as courtyards, screens, and recessed windows. The pedestrian spine serves as the main connection between the cluster of houses and the communal amenities of the neighborhood. The MOFA housing project was later emulated in the al-Hamra neighbourhood in Riyadh. Another large housing project was formed under the development plans for the diplomatic quarter at the time.

In an attempt to search for an identity for the Saudi urban environment, several architects adopted local and other Arab traditional elements and concepts in their designs. This somehow echoed postmodernism movements that were a prevailing theme during that period adopted world-wide. These approaches were aimed at creating regional identity in architecture based on utilizing traditional or vernacular elements.

By the late 1990s the city experienced an unprecedented growth in the rate of population, which led to vital redevelopment plans and strategies. Despite the requirements to increase density in sub-centers, dwelling types and plot sizes remain similar to those earlier housing models. Recent examples of Saudi villas can be described as a cross between western influenced villas appropriated to fit the Saudi family needs. For example, separate male and female reception rooms were built in the front part of the house to accommodate hospitality traditions. A family living area is introduced within the house for informal family activities and kitchens are often detached or closed off from main living spaces. Relatively popular residential architecture in Riyadh can be characterized by use of elements and vocabularies borrowed from vernacular traditions in attempts to revive and reinvent them, these practices are as much the product of the clients as the architects.

Expanding horizontally has often been the nature of Riyadh’s development; however, there have been attempts to densify centers such as King Fahad street with high-rise development and thus prompting vertical growth and expansion. There have been several municipality restrictions regarding building heights in other districts. The Financial District has recently been introduced to revitalise this attempt, where it serves to accommodate 12,000 residents in 24 apartment buildings.

The metamorphosis of the Riyadh house emulates the changes in our lifestyle in relation to the space we inhabit. From adobe mud houses to neo-classical concrete villas, our efforts to rehabilitate the city’s identity and unify its architecture methodology will become a major focus in order to solidify our contemporary approach to Saudi living. Environmental and economic considerations will most likely play a major role in forming future housing typologies. Environmental and economic considerations will most likely play a major role in forming future housing typologies. In addition, efforts should be given to understand how we utilize and interact with our built environment and the effects of form and materiality on shaping our living experiences.

Research by: Sara Alissa | Nojoud Alsudairi

Riyadh Map

Riyadh City buildings, Wihelm von Schreeb, Sweden

Nasiriyyah palace, Riyadh Newspaper

Mohammad Bin Fahad Building, Twitter

Villa in Almalaz, Mediterranean House of Human Sciences

MOFA Housing, Agha Khan Award